Hello everyone,

As you may know, we are in the final stages of wrapping up the second edition of Gamestorming. It’s been 15 years since the first edition, so it’s about time! Our publisher, O’Reilly, has been kind enough to allow us to pre-release a couple of chapters. This is the first one. Please note that this is raw and unedited (for example, this is chapter 3 and it references chapter 4 as a previous chapter!), but we’re sharing it with all its flaws. We still have lots of editing to do, but we don’t want that to get in the way of getting it in your hands. Please do share any thoughts in the comments.

We will share another pre-release chapter in the coming weeks.

Pre-order your copy of Gamestorming 2.0 now!

Chapter 3: Designing Workshops and Meetings (and games!)

A Note for Early Release Readers

With Early Release ebooks, you get books in their earliest form—the author’s raw and unedited content as they write—so you can take advantage of these technologies long before the official release of these titles.

This will be the 3rd chapter of the final book.

If you have comments about how we might improve the content and/or examples in this book, or if you notice missing material within this chapter, please reach out to the editor at shunter@oreilly.com.

Whether we’re conscious of it or not, ordinary life has rules. Secret signals, implicit norms, and explicit codes of conduct form what cultural psychologist Michele Gelfand calls a primal template of culture–an elegant way of describing how we do things around here.

Meetings also have cultural templates. They’re revealed in our default versions of gathering at work, which almost no one seems to delight in. Meetings as we know them tend to be too tight or too loose, too vague or too prescribed, too joyless or too chaotic - and definitely far too frequent. Few organizations have solved the meeting puzzle in terms of people, process, path and product, so meetings end up being almost tragicomic, unsatisfying for most attendees most of the time. This is hardly a revelation. Meetings are the butt of countless jokes about modern work. At best, they’re a groan-worthy, minor inconvenience. At worst, they’re a sign of partial attention, scattered focus, oblivion and disrespect.

Disrupting the default meeting template

When entrepreneur David Hieatt was designing the culture of Hiut Denim, inspired by Cal Newport’s research on deep work,1 he drafted a set of team guiding principles. One standout on the list: Protect employees from dumb meetings. As the CEO of 37 Signals pointed out, “Five people in a room for an hour isn’t a one-hour meeting. It’s a five-hour meeting.” Designing this time well matters, and that’s why this book exists: to positively disrupt default meeting templates and share a unique, multisensory, effective approach to bringing people together and making them glad they came.

Accomplishing that doesn’t have to be complicated. You don’t need to be a seasoned meeting planner or any version of a meeting guru to quickly improve on the default experience. If we decide to, any one of us can counteract the life-draining forces of ordinary meetings. Any one of us can identify a problem that warrants a meeting, gather the energies of a group, and help point that energy in a valuable direction. By now you know that we do this through games and we call our practice gamestorming.

It should be stated outright that it’s okay to be allergic to the words ‘game’ or ‘gaming’ at work. Games have varied connotations that aren’t associated with this practice including zero-sum competition, psychological manipulations and hidden agendas or, on the flip side and god forbid, having fun. Discouragingly, it’s the last one that seems to be the most taboo!

On the surface, work is a four-letter-word that designates NOT enjoying yourself, and managers don’t necessarily applaud us for having a good time. In Chapter 2, however, you learned how we define a game. Our kind of game is one that positively disrupts the default meeting template by approaching any challenge through a series of thought experiments – multisensory, interactive, intentional thought experiments. Gamestorming makes things happen, and if fun is a natural byproduct, so be it. Learning and solving should be fun - it makes problem-solving more fluid and effective. Gobs of research supports that2, and so does direct experience.

We’ve applied this method for over 20 years and its aliveness continues to surprise us. As one of our global gamestormers expressed, “[This practice] inspired me, and a whole community of people, to understand how we can be (should be) together when fully immersed in collaboration at work. It changed how we viewed ‘work.’ It brought creativity, design and co-creation to a new group of people to show them what’s possible.”3

When you are designing a meeting or workshop–which typically involves a sequence of games–you want to think like a composer, orchestrating the activities to achieve the right harmony between creativity, reflection, thinking, energy, and decision making. There is no single right way to design a game. Every company, and every country, has its unique culture, and every group has its own dynamic. Some need to move faster and more playfully than others, and some need more time for deep or silent work and reflection.

For example, in Finland, long silences where people consider and reflect on a question before answering are not uncommon. This can feel very uncomfortable if you’re not accustomed to that culture. You’ll need to do your homework and compose a flow that’s right for the group you are working with, and the situation you are working on.

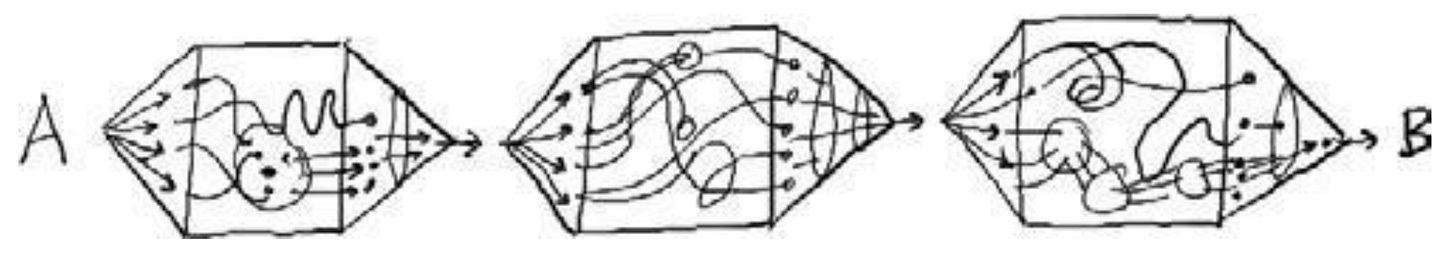

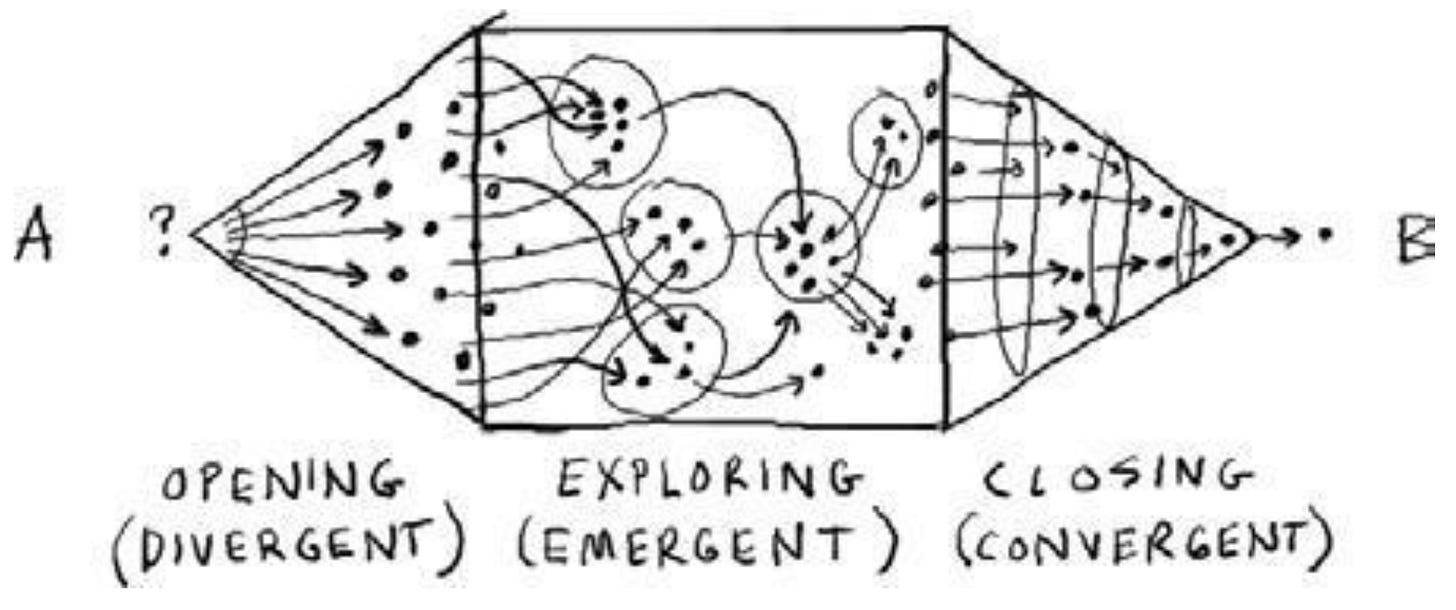

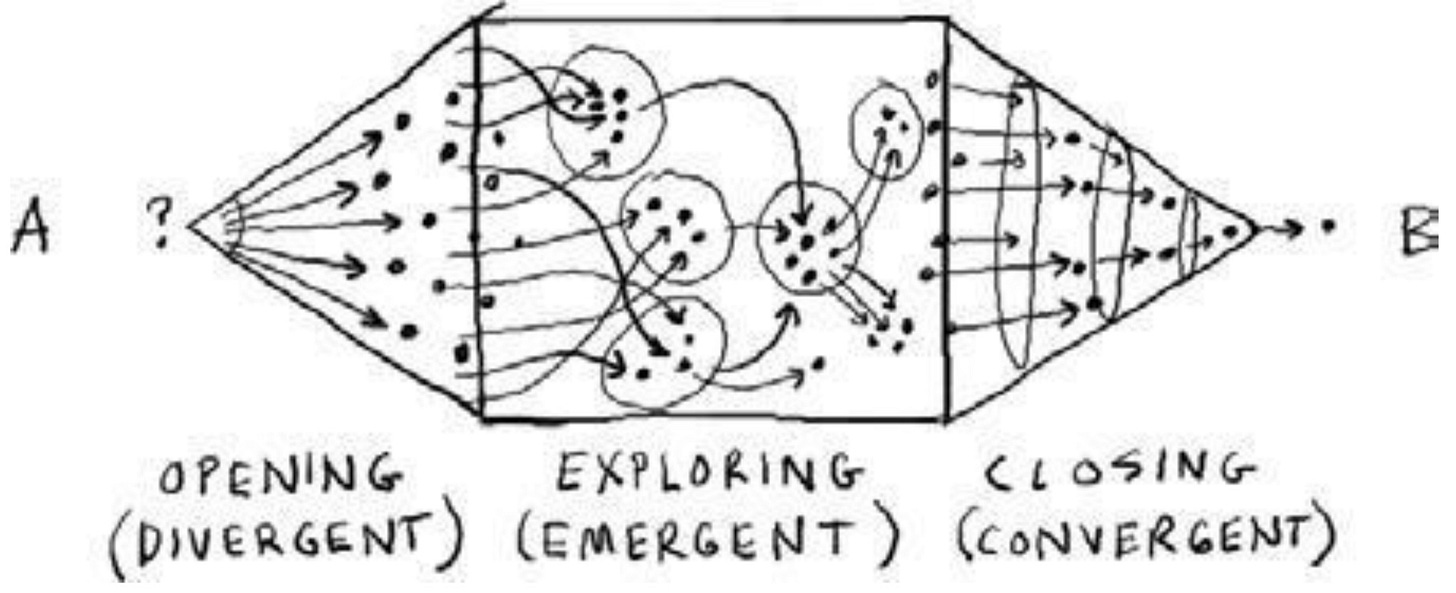

Opening, exploring, and closing is a core meeting (and game) structure that will help you orchestrate the flow and get the best possible outcomes from any group. A typical daylong workshop may be filled with many games that can be linked to each other in an infinite variety of ways. Games can be, and ideally are, played in series, where the outcomes of one game create the initial conditions for the next.

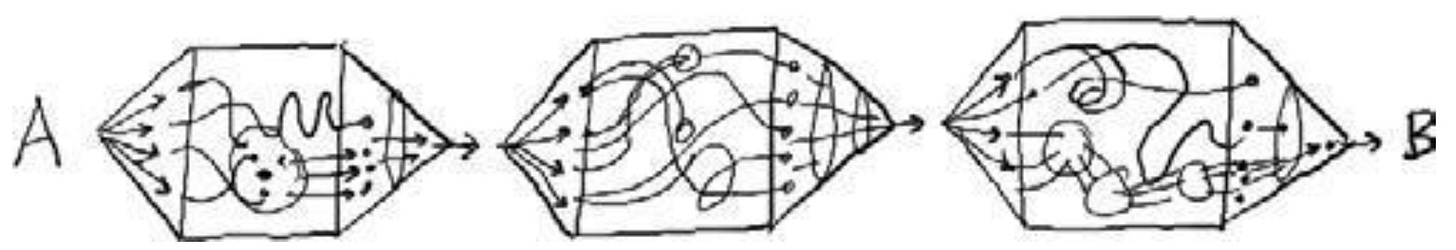

Below is a series where three games are played in a row. Each game has a clear opening, exploration, and closing. The outcome of each game serves as the input for the next. This kind of design is simple, clear, and easy for everyone in the group to understand.

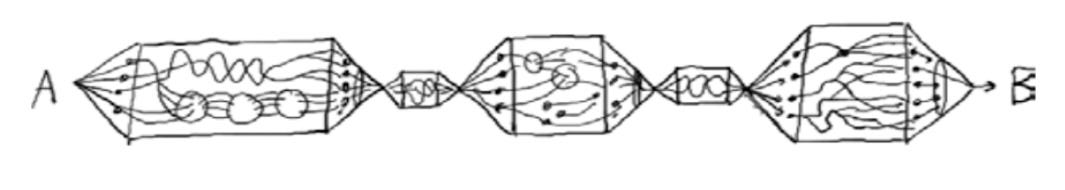

In the next series, three longer, more intensive games are interspersed with two shorter games. The shorter games might give the groups a chance to loosen up a bit between more intensive activities.

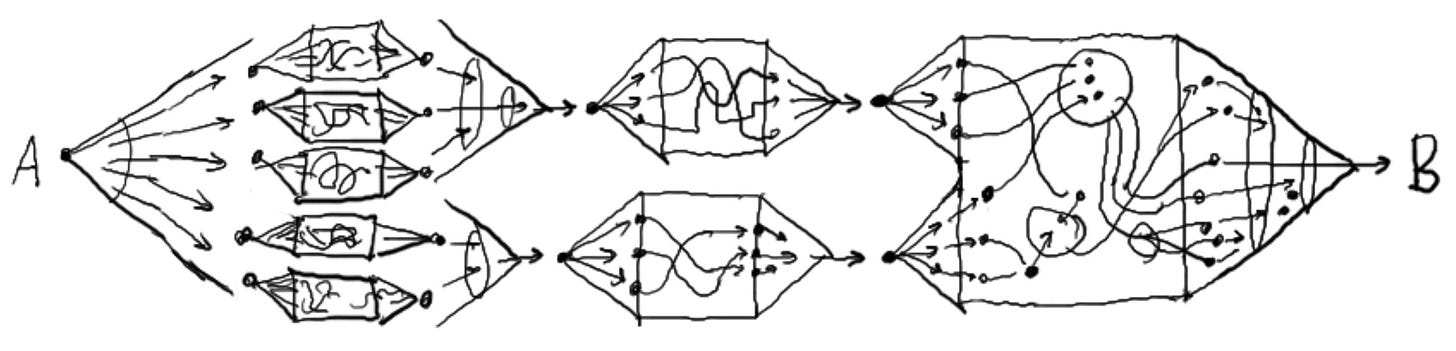

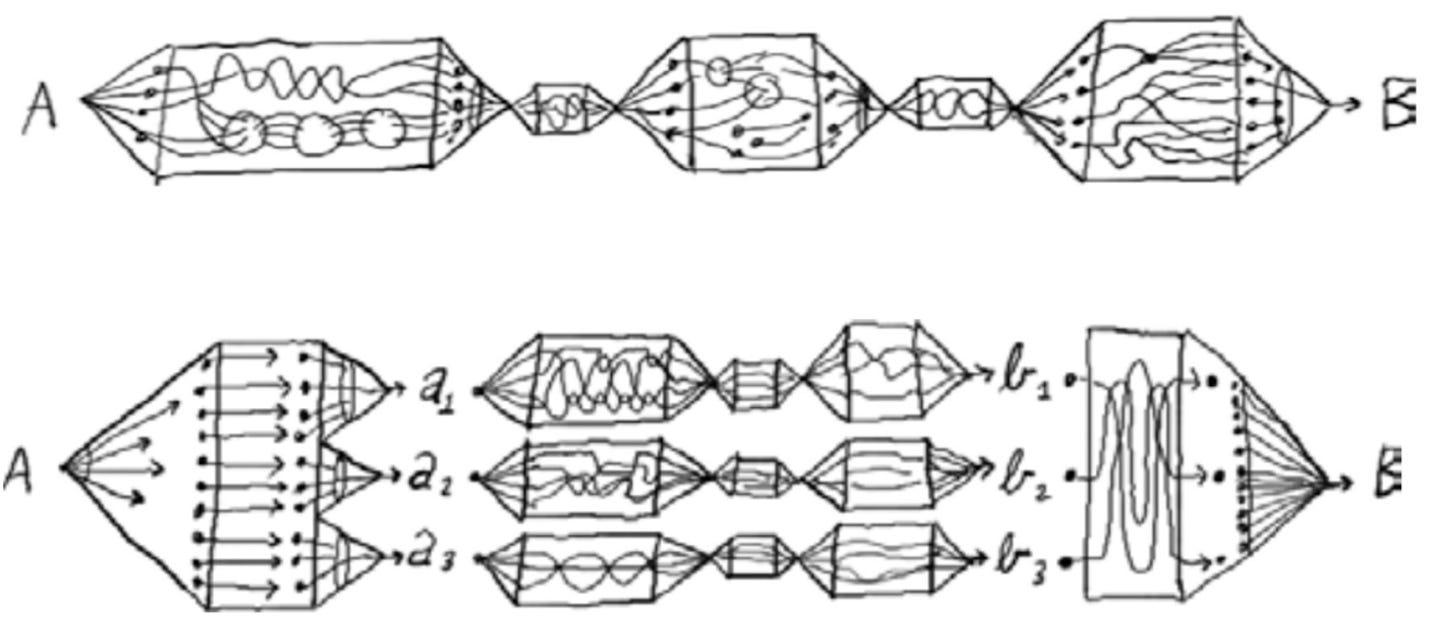

Sometimes, especially with a larger group, it makes sense to pursue multiple goals. A key concept in game design is a variation on opening and closing called break out/report back, where a larger group diverges by breaking out into smaller subgroups, plays a game or two, and converges by reporting back the outcome of their efforts to the larger group. This is a way to keep groups small and dynamic, and also increase the variety of ideas, by playing multiple games in parallel.

People also need time to reflect on ideas. Breakouts (or breaks) can be a good time for this. Break out/report back is a way to balance sharing and reflection and to create quiet time. For example, you can ask people in a group to spend time working on an individual exercise which they can then share with the group.

Here’s a series where an initial, opening session reveals three different goals that can be pursued in parallel breakout groups. At the end of the series the three groups’ outcomes are shared in a report-back session with the larger group.

Here’s a series where the outcomes of the first game generate inputs for five games, which generate inputs for two games, which generate the input for a single, longer game. This kind of string might indicate a workshop including multiple ideas and agendas that need to be worked on in parallel.

Here’s a daylong game where a big chunk of the morning is spent on divergent activities, generating a lot of ideas and information, and the exploration phase is split into two parts, with a break for lunch, followed by an afternoon of convergent activities that flow into a single outcome. The group will lunch together at four tables for informal conversation and reflection on the morning’s activities before going into the afternoon session. This kind of design might be appropriate for a group where everyone had some level of interest in every component of the day, and nobody wanted to be left out of any part of the game.

Sometimes you make discoveries while a game is underway that require a change in direction. In the following series, the initial opening and exploration revealed a new goal that the team had not anticipated. The group agreed to break into two subgroups; one group pursued the original goal and the second worked on the new goal.

OK, so it’s time to compose a game, or maybe a series of games. Where do you begin? What do you compose with? Remember that gamestorming is a way to approach work when you want unpredictable, surprising, or breakthrough results—a method for exploration and discovery.

It can be helpful to remember that there are no guarantees in creative work. You are searching for something that you may not find. You will almost certainly find things you don’t expect. You have only a vague idea of what you will encounter along the way, and yet, like a turtle, you must carry everything you need on your back.

The 7Ps

With just a little bit of orientation and effort, you can onboard quickly and gamestorming can be simple. It layers and deepens as you go. The first thing that can give you confidence is our tool called The 7Ps.

In this book, we are not aiming to build an army of hard nosed, clinical meeting technicians. We’re aiming to democratize visual thinking and experiential ways of working, to empower every person to improve any meeting experience. To that end, we want to outfit you with tools of various shapes and sizes. One of those tools is THE tool to consult any time you’re tasked with bringing people together. Think of it as a recipe for learning to transform not just one meeting, but overtime and with providence on your side, your entire meeting culture. Like a great meal, a great meeting also requires contemplation and planning in advance. Think of the 7Ps as your secret recipe, one you can count on and return to to increase the odds of a crowd-pleaser.

Let’s talk a walk through each of the Ps so you can slowly take them in. How about we begin with that North Star: Purpose.

PURPOSE

I know some of you reading the word ‘Purpose’ will be surprised at the requirement to include it. Surely people don’t bring others together without knowing why they’re doing it?! Indeed, we do it all the time. Some of us are social creatures and we gather people out of our own biological requirement for extroversion. Some of us are people who have to think out loud with others–verbalizing, externalizing, and socializing thoughts in order to think better. Some of us are spread thin and moving so fast we haven’t slowed down long enough to consider what the hell is going on. And still others of us are so accustomed to the absurd and pointless default meeting template that we’re unconscious to it, resigned to our fate.

To be a gamestormer is to become conscious of the default meeting template and own your conditioning around it. This doesn’t have to involve a huge leap. Determining the purpose of a meeting can take 30 seconds if you know your team, the context, and the project or strategic initiative y’all are focused on. Simply imagine yourself in a room with those stakeholders and ask yourself the essential question, Why are we here? You can often get a good insight right away. In this case, it’s the upstream act of choosing to pause in order to make the purpose explicit that can require some effort.

In other situations, the discernment of purpose may require a bit of mental gymnastics. The latter, more complex circumstance, is worth examining.

We’ve discussed that a gamestorm can take anywhere from 30 seconds to four or five days or beyond. Shorter meetings–those that last 20 to 60 minutes, for example–are relatively easy to design. But as the time spent lengthens, or the number of stakeholders increases, and/or the size of the challenge being addressed scales upward, the arc of an experience will need to be more crafted in order to be valuable, and determining a meeting’s purpose(s) will first require two crucial skills: great questioning and deep listening.

Sensing Interviews and Meeting Goals

People responsible for a meeting or workshop toward the longer end of the time spectrum will generally have a sense of what they want to accomplish, but it can become the job of a game facilitator to seriously kick the tires on their perceptions and assumptions before designing, or helping design, the meeting experience. I use what I call ‘sensing interviews’ to help them begin. Those interviews involve the kinds of questions you read about in Chapter 4.4 Like any good design scoping process, the aim of these interviews is to help a person responsible for the success of a meeting precisely identify two types of meeting goals: Explicit and implicit.

Explicit meeting goals are those that directly point to a tangible deliverable(s). These are goals that, if not met during the time spent, would make the meeting a failure in the eyes of the stakeholder or client. A tangible deliverable might include a process map for on-boarding new employees, the establishment of criteria for a future product, a revisioning of an old vision statement, or consensus around next steps for an ongoing campaign.

Implicit meeting goals are the subtle and subterranean, often equally and sometimes more important, goals of the time spent together. These types of goals include relationship-building, deeper on-boarding, the reification of cultural or desirable norms, the smoothing over of known conflict, changing perceptions, social bonding, and so on. Both of these types of goals matter, and they tend to matter more as the duration lengthens.

When designing a meeting, many people blow past this process of discernment and jump right into meeting design, or they identify explicit goals but neglect putting attention on implicit goals. Both moves are a mistake. It’s far better to be patient, go slow, and ask intelligent, bold, and nuanced questions at this scoping stage. If you do, you’ll have more confidence that when you put together a sequence of games, you’re helping the group solve the right problem, the one that would best serve their needs at this juncture.

Deepening the Skill of Sensing Interview Questions

There are scores of books that offer examples of excellent questions aiming for discovery, so don’t imagine there’s some “best set” of inquiries. This stage of meeting design is much more about your willingness to engage in clear, sometimes courageous, probes and pay close attention to the responses while minimizing the overlay of your biases, or at least bringing them to awareness and putting them on the table for inquiry. It is then your task to help the meeting lead or client (or yourself, if it’s your meeting) sense into what’s needed–intellectually, emotionally, intuitively, operationally, and strategically. Most likely, she already has the first-level answer to the purpose of the meeting but could use space, time and supportive attention to go a few levels down, homing in on a deeper knowing, kind of like a heat-seeking missile.

The most important aspect of the questions you ask while in sensing mode is that they be open-ended. Ideally, some of the questions involve the client telling real-world stories – about the team, the culture, the state of the organization, why this meeting now, what efforts the team has made in the past to attend to the challenge, and so on. Your job at this stage is to create conditions for deeper insights to become available, then capture that wisdom as it emerges, reflect it back to the meeting lead, and design for it.

Below are more examples of the sensing questions we previously defined (see chapter 4: Gamestorming practices). It helps to have rigorous question sets and we’ve used these many times to discover the purpose and goals of a meeting or workshop so we can design more intelligently. Keep in mind these are just examples; they’re not the Holy Grail. It’s always a useful endeavor to exercise your muscles for imagining and inventing questions.

Opening Questions

Recall that opening questions provoke thought and reveal possibilities, opening doors to new ways of looking at a challenge. Some examples of opening questions to help you design a meeting might be:

What are your hopes or desires for this workshop / session / meeting / gathering?

What is really prompting the desire to arrange this meeting?

In this scenario, what would a wildly successful meeting look like?

If you could accomplish a surprising amount of objectives in this period of time, how would you do it?

For this session, what’s relevant about the state of the organization? What’s relevant about the state of the industry?

Paint me a picture of what would happen if this meeting didn’t take place.

Navigating Questions

Navigating questions set the course, point the way, assess, adjust, and correct for errors.

If we were to get the group to this desired insight or understanding, where might we go from there?

If you had to kill one of your meeting-goal darlings, which one would go first? Second?

What aspect of this session is expendable if we were to run out of time for any reason?

How would you redesign the stakeholder groups if you wanted teams to help identify unseen obstacles in other teams’ worlds?

Examining Questions

You read in Chapter 4 that examining questions are about observing and analyzing, focusing on details and specifics, and noting observable characteristics.To examine the possible best direction of a meeting, you might ask:

What has caused past brainstorms to fall short or fail? What have been distractions or impediments to the robust exchange of ideas?

Describe the interpersonal dynamics among the people attending this session. Say something about their familiarity with each other, their history, or the history of the team’s role in the bigger picture of the organization.

What has made past sessions successful? What conditions or dynamics helped assure the desired outcomes?

What are current changes or trends happening in the industry that influence this group’s thinking?

What elements of your product, service, or experience are up for reexamination?

Experimental Questions

Experimental questions are powerful questions because they invoke imagination, take people to higher levels of abstraction, and purposefully awaken the possibility of seeing or doing things differently. These questions might be related to the goals of a meeting or to the experience design of a meeting itself.

What if success for this project were completely redefined?

What would happen if we left leadership out of this meeting?

How might you add a constraint in order to boost creative thinking?

What if the user base for this product were another community entirely?

Imagine a scenario in which your users became your advisors.

How would this meeting be conducted if we designed it using no slides and including no planned presentations?

Closing Questions

Remember that closing questions converge and select, rank options, help people move toward commitment, make decisions, and take action.

Are you present to anything you’re not saying about this meeting and the people participating?

Here are explicit and implicit goals that have come up in this conversation: Can you give us your perspective on them? Do some need to be edited, added, or removed?

Rank these outcomes of the meeting in no uncertain terms.

Even though this meeting is positioned as an exploratory, open-ended brainstorm, can you speak to meeting outcomes that leadership is ultimately aiming to drive people toward?

In sensing interviews, the richness of an answer or response is so profoundly influenced by the power of a question that these question categories bear repeating. Developing your ability to inquire with texture and depth will very much serve your gamestorming skills. At the end of the day, each game, in its own way, asks a question and leverages group intelligence to respond to that question. And as a game facilitator, your opportunity is to skillfully curate those games - to help players open, explore, and close those worlds - one after the other in a meaningful path we call a game sequence. We’ll go over game sequences in the section called ‘Process.’ First, let’s examine that second requirement for designing great meetings: deep listening.

1. Deep Listening

Deeply listening to another person is a gift to that person and to ourselves.To quote author David Augsberger, “Being heard is so close to being loved that for the average person, they are almost indistinguishable.” Now, as a gamestormer, it’s not your work to learn to love your client but it is your work to listen closely to them before you attempt to build an experience that serves. This section is about the listening work that needs to happen in order to design a fantastic meeting or workshop, but it’s also relevant to note that deep listening is a crucial skill for leading and facilitating that meeting as well, if that ends up being part of your role. Great facilitators are necessarily great listeners. Learning to listen deeply will serve you well in every area of your gamestorming practice - from beginning to end - and also in your life. Let’s look closer.

The infographic below shows a model for listening inspired by my collaborations with therapists, coaches and great facilitators. There’s a lot to it so review it at your leisure. The headline is that deep listening happens in the absence of our own judgments and opinions. It is easy to allegedly “listen” with our personal internal chatter running in the foreground of our minds, issuing all sorts of evaluations, retorts, assessments and critiques. It takes practice to listen with that in the background, or better yet, to listen with it not running at all. The outer circle of this infographic designates what it looks like to NOT be listening. When we’re being emotionally honest with ourselves, we can see how much that outer ring resonates with how we usually operate.

Where we aim to go is toward the inner circles. As we move closer to the center, which is the seat of deep listening, our own egoic pursuits start dropping away. We learn to stop listening for our turn to speak, to stop listening solely to assert ourselves and show our dominance or intelligence, and we learn to start listening with the sole aim of intimately knowing someone else’s view of the world.

For many people, a quick hack to do this thing that sounds, and is, pretty hard is to think of yourself as an anthropologist. Take a backward step and try to remove yourself from the action of the moment. If we can shift into observing-mind, we have a better shot at softening our own perspectives and ideas and making space for someone else’s.

Anthropologists don’t necessarily listen with empathy but they do try and pay attention with a more receptive mind. They try and drop preconceived notions of what they’re witnessing and make space for information that’s at least slightly less polluted by personal interpretation. It can be done with commitment and a little effort. Luckily, opportunities abound to practice and you can always check your view of reality by summarizing your perceptions and running them by the client. Good gamestorm design doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Your selected thought partners and collaborators can and should be included to check your assumptions, views, and decisions.

The skills of great questioning (accompanied by deep listening) create a container for solid meeting design. Gamestormers working toward mastery should purposefully prioritize and strengthen these capacities. They’re among the secret sauces for compelling meeting design and they help cement a real sense of purpose as we work to solve problems together. When we get into process, the value of these skills will be even more apparent. First, let’s talk about People.

PEOPLE

If I had a dollar for every time a friend or colleague texted me behind-the-scenes to say “Why the hell am I in this meeting?” - it’s safe to say I’d have an extra vehicle. Just as it’s common for the Purpose of a meeting to be poorly- or undefined, it’s also common for a smattering of the right and wrong people to be in attendance. But as noted above, a one-hour meeting involving five people is a five-hour meeting, so it pays literally and socially to steward the participant list.

For most meetings, this exploration doesn’t require a concerted cognitive effort. Is this person directly involved with what’s being discussed? Will he, she, they have something crucial to contribute? Would their absence create a strategic, tactical, or logistical problem?

For explicit meeting goals, you might think in terms of questions and answers. Who are the people you need in the room to answer the questions you have? For implicit meeting goals, you can think in terms of relationships, influence, and group needs. Whose presence encourages openness and transparency? Whose leadership qualities give people courage? Who has deep experience with the landscape being explored in the meeting? Who inspires curiosity? Who is the keeper of the history we need to know for this session? Even if that person or group isn’t responsible for the final deliverable, their presence may create a much-needed fluidity, or add valuable but more subtle knowledge, to help that deliverable emerge and improve.

Consider both types of meeting goals - explicit and implicit - and weigh those goals against the know-how, presence, and the gifts of each possible participant. Then choose wisely. Choose even more wisely if the meeting has constraints you can’t correct for - like a requirement to travel, physical space limitations, time-zone restrictions, or needs for confidentiality. If the participant list is necessarily limited by these kinds of constraints, it’s important to designate post-session communicators or communication deliverables - people or artifacts that can convey the informational and actionable exchanges if everyone you wanted to couldn’t attend.

PROCESS

Designing the arc of experience for a meeting is one of the two main areas where gamestorming chops get refined – the other is in the arena. The overarching question related to Process is, What sequence of games will inspire, compel and move this group in an engaging and intelligent way toward the Meeting Purpose, Goals and Product? Inside of that question are truly infinite answers. Games and game mechanics are endless, which means process design is the most divergent and creative P among the 7Ps. It’s also where you as a game facilitator have the most opportunity to collaborate in advance with stakeholders or attendees, if either of those options make sense.

Our teams have designed a surprising number of game sequences over the last 17 years, and we’ve run those sequences with groups ranging from 4 to 5,000 people in built environments of every shape and size - board rooms, museums, auditoriums, theaters, classrooms, rooftops, and offices almost as small as closets. The world of games is boundless and very much choose-your-own-adventure, as long as you keep the endgame in mind and are present to the norms of the culture, even as you may seek to expand them.

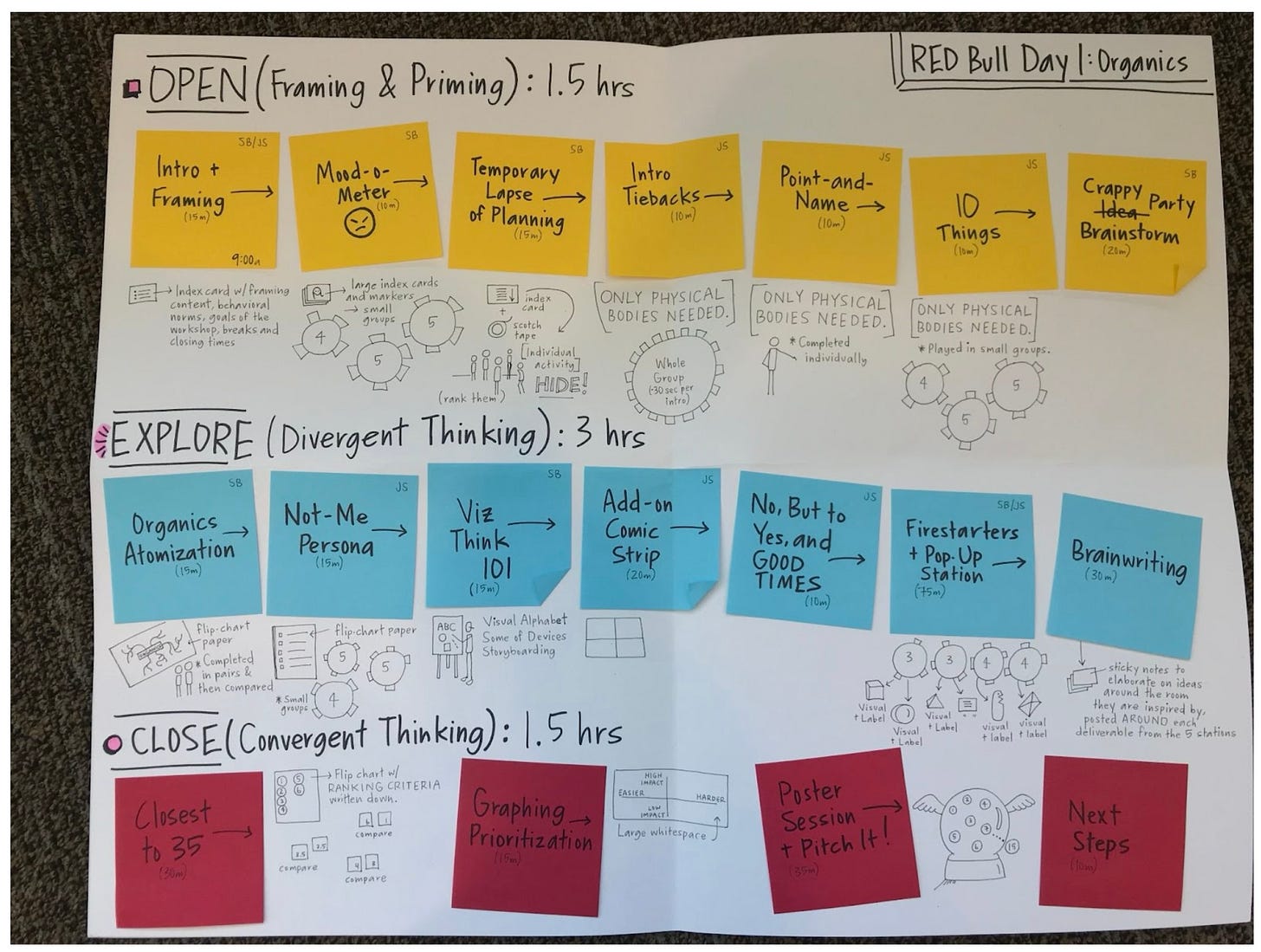

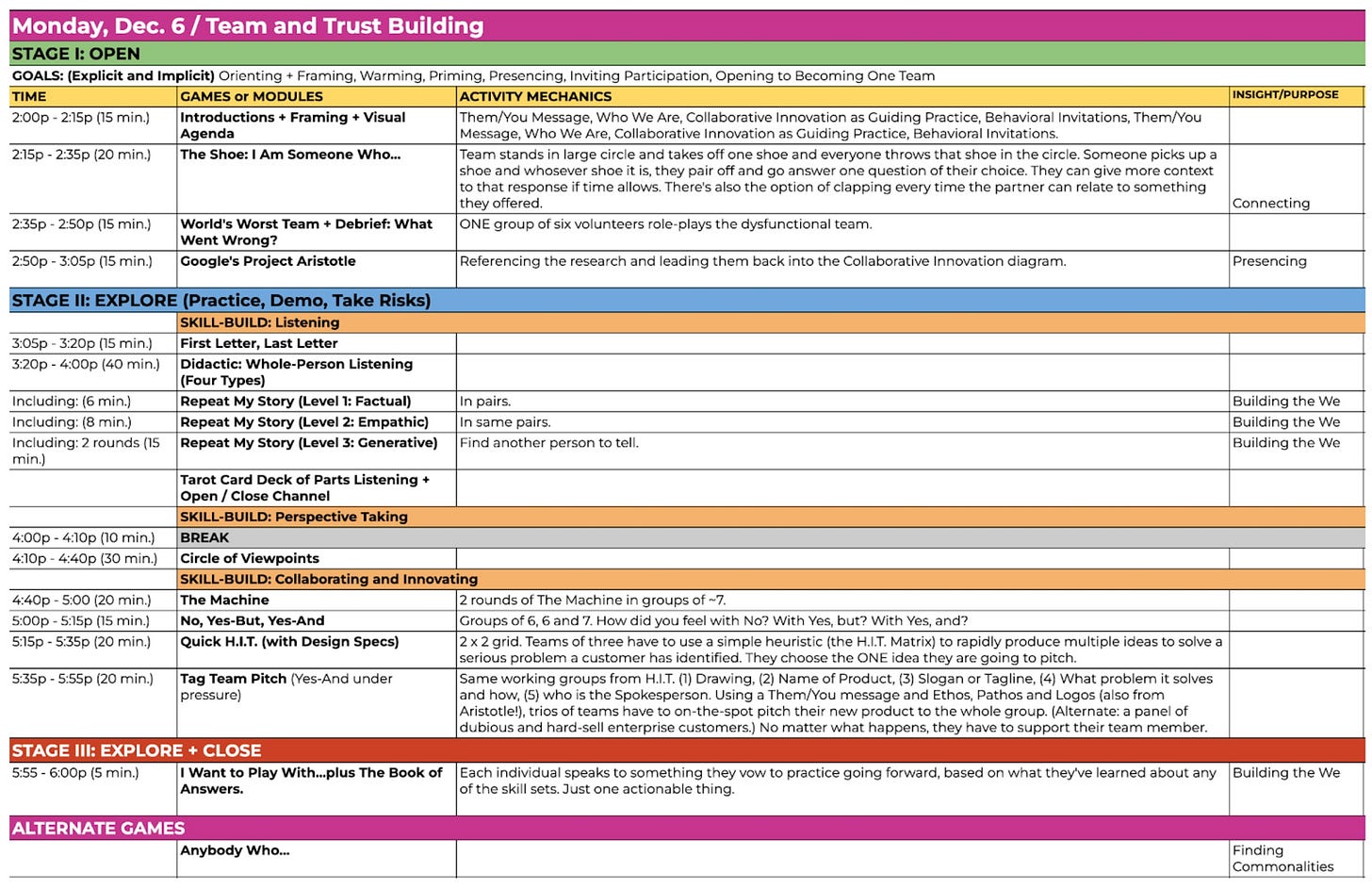

Below you’ll see examples of meeting agendas we’ve designed in software like Excel, Session Lab, Trello, and MURAL. We’re agnostic about the tool you use to document the agenda and meeting flow. What matters chiefly are those structures of Opening, Exploring and Closing that we discussed in Chapter 2, and that you’ve imagined and built the world well.

What also matters is how each individual game selected interacts with the games that come before and after, and how the combined sequence of games serves the participants as well as the meeting goals. This image below represents one game - for example, The Blind Side - and it reminds you how each game is its own self-contained unit of activity and energy, a unique thought experiment ushering us onward toward a (sometimes fuzzily defined) horizon.

Even short meetings - perhaps a meeting with three games each lasting approximately 15 minutes (a structure shown in the next image) - provide an opportunity to do something good, or even great. Participants working in a gamestorming fashion almost always emerge more energized and you can easily turn something like a typical stand-up meeting into a fantastic gamestorm.

Longer meetings generally have more complex underlying structures - the next image below shows a sequence of five games of differing durations, and still other meetings can become even more elaborate, like the image after that where an initial, opening session reveals three different goals that can be pursued in parallel breakout groups.

The vast majority of your design decisions will be fueled by those early Sensing Interviews. That discovery process informs the depth of your understanding and it’s the ground from which Purpose, Goals and Product spring. When you get down to brass tacks and start plotting a possible sequence of games for a meeting, the sky is truly the limit so here are some key areas to be mindful of as you consider game selection.

GAME

DURATION

INSIGHT/PURPOSE

GAME MECHANICS

Designing an agenda is an iterative process so in round one, you’re taking an initial swipe at a path of play. We do this first round in both analog and digital spaces, and our goal initially is to play with possible options that might point toward the horizon designated. You’ll see in the game section of this book that there are durations assigned to each game, so we loosely make notes of that duration as we plot the path on sticky notes, as in the example below.

When you start designing, you’ll almost always know the total amount of time you have with a group and that time is where you’re constrained. Within that bigger time block is where you can plot games along the span of time. That part is relatively easy. It’s selecting and sequencing the games that requires a mental and imaginative workout.

SELECTING AND SEQUENCING GAMES

How we think about game selection and game sequence is mult-faceted. For your typical stand-up team update, you can select games that you know play well together and have become “old reliables,” These may be Core Games or games for exploring like Forced Ranking and Stop-Start-Continue. But for a meeting that has more potential, there are considerations for game selection that include crucial understanding of both the Insight/Purpose of the game as well as game mechanics. In each game chosen, those aspects of it need to thread together effectively throughout.

Facilitating games and activity set-up

One of the most common ways Gamestorming meetings can go wrong is in the design and set-up of an activity or exercise. We recommend that you script your instructions and rehearse in advance of the meeting. Try to keep exercises short and instructions clear. Resist the urge to ask people to remember multiple steps. If you want people to do multiple activities, we suggest you reduce their cognitive load by breaking them up into short sequences. For example, if you want people to do an activity with three steps, have them do the first step, then reconvene and make space for questions or reflections, before moving on to the next step.

Insight / Purpose of a Game

As noted earlier, every game is a unique and individual thought experiment out of which comes a set of semi-predictable insights that respond to the input or provocation of that game. For example, the input of the thought experiment of Pre-Mortem is a single question, What could possibly go wrong? The output is a collection of thoughts and ideas from the group about that very thing. For a game sequence to be coherent, that output needs to flow with ease into the opening of the next game, almost like a chapter in a storybook.

Using the example of the Pre-Mortem, let’s say the group has brainstormed potential missteps and are leaning into the next game. The question is what game(s) might be useful to open right after they’ve generated these insights? There are many diverging options. Your next game could involve a thought experiment around co-defining specifically what they’re trying to do. Or the group might be served by turning their attention to what things have actually gone wrong in the past and extracting lessons learned. Or the next game could double down on what would go wrong, asking the group for hellish scenarios to go the distance in using our powers of catastrophizing.

The aim here is to use the content generated by a game in order to keep the energy moving. A good game sequence will leverage the information surfaced from one game and move it, often seamlessly, into the next. As I work to build an agenda game by game, time block by time block, I ask myself:

What does this particular game help the participants do? What kind of thinking move5 does it help them make? What are the learning outcomes and insights of this game?

What is useful and needed at this node in the meeting experience? Do the participants need information in order to take action? Do they need time for reflection of something they just absorbed? Do they need to socialize their insights and create together? Once I have a sense of what’s needed or what would serve at each turning point in a meeting agenda, I can evaluate games based on that need.

If I chose the game, does it flow nicely after the one before? Does it segue well into the one that comes after? Did the game before set this game up for success, and does this game set up the next game for success, too? Does this game sequence flow? If so, how well?

To take it to an even more attentive depth, because gamestorming is ideally deployed with attention to learning styles, energy levels, and the spectrum of introversion and extroversion, you might also consider the following:

Is this an individual game or a collaborative game? Do introverts need downtime at this intersection in the agenda?

How intense or challenging was this game for them mentally? Would this be a good moment in the agenda for lightheartedness or levity?

What sensory modalities are involved? Visual? Auditory? Musical? Kinesthetic? Mathematical?

How long have we been in this room or game space? Does the group need to shift their attention entirely? Go outside to change states and come back to try again?

Does this game feel like something that would resonant with the culture we’re facilitating for? If not, does it help them expand and grow in ways that will be useful?

If leadership needed to intervene with a presentation, thus disrupting our game flow, does this game follow nicely with the content of their keynote or talk and still meet the needs of our agenda?

Game Mechanics

The mechanics of a game refer to just what it sounds like - the working parts of a game that give it its own locomotion. Mechanics are about how the game runs on a functional level. To take this entirely out of abstraction, let’s look at the simple game Post Up. Post Up involves players generating ideas related to a question and writing one idea per sticky note in response to that question and posting all of their sticky notes on a wall. The mechanics of that game are simple: Jot down an idea. Post the idea on the wall. The output of that motion are flurries of sticky notes that show individual ideas.

To move into the next game, those sticky notes, or the information on them, needs to somehow become usable. So, do you cluster all of those sticky notes in terms of similarity? Do you move them to different walls related to roles? Does someone read them aloud while breakout groups choose which idea they want to pursue? The mechanics of the closing of one game need to be sorted with the opening of the next.

In an uncomplicated or seamless world, the mechanics of a game wouldn’t be something that requires serious attention, and often you can get by without pinpoint precision. The information generated can readily keep going. Other times, you’ll need to really think through how the artifacts of each game may need to be pulled along, sometimes across multiple games, in order to arrive at the endgame in a meaningful way. Crucial questions to ask relative to game mechanics are:

What materials are needed to successfully run a game and are they already in place or does that require effort or a pre-designed object or artifact?

What artifacts will emerge from a game and how will those artifacts be plugged into and inform the next game?

Below is a gameboarding template that can help you consider a game sequence. This is an experimental space for you to write names of potential games, plot them on this board, then sense into and evaluate how that arc of experience would feel for the group. Does it accomplish all that you’ve set out to do? Does it lead them toward the goal, however fuzzy? Does it honor the Purpose of you all getting together? Does it engage as many of their sense as possible? If so, then you may well be onto something.

The more you build up your encyclopedia of games (and eventually, gain confidence in inventing your own!), the more options you have to build a dynamic and impactful experience. Take creative and intellectual risks. Don’t play it safe with games you already know and love. Honor the energy and attention of the people in the room by really contemplating the efficacy and process of what you have designed. Think of yourself like a chef putting together the best possible menu for the situation at hand. How can you best delight? How can you best serve?

PRODUCT

The meeting product is the high-value, tangible deliverable(s) that ultimately shapes the arc of experience. It’s that which you can sink your teeth into, that which you can wrap your mind and hands around once a meeting closes. The product, therefore, is the thing that gives you confidence in choosing the directionality of your meeting even while, in true gamestorming fashion, that direction may include some diversions, some exits and re-entries, maybe even some meanders. Remember this image?

Your meeting Purpose - why you’re there, the implicit and explicit goals of the meeting - is directly influenced by the desired Product in that the Product is the tangible endgame and the meeting Purpose should be harmonious with that endgame. The Product can be qualitative or subjective, something like helping the team to bond, but more often than not, clients or stakeholders want a specific thing. They want a budget hammered out; they want a strategy document; they want a signed team declaration of values.

Every step of the way, the Process you design is intended to get them there in ways both tactical and creative. What’s good about thinking of a meeting in terms of including a Product is the clarifying effect that knowledge has. When participants know they’re responsible for producing something actionable or deployable after getting together, they tend to buckle down and focus.

PREPARATION

This P doesn’t refer to your preparation as the game facilitator or meeting lead. You’ll find that insight in Process. This P refers to ways you might help the participants prepare for the workshop. In reality, unless there’s a cultural mandate or a really motivated team, many participants won’t carve out the time to do preparation even if it’s brief (unless their failure to do so will somehow show in the end product - and you can design for that). Nevertheless, some participants will do work in advance, and it can help to seed the upcoming conversation with information that orients, inspires, or informs.

Examples of information that helps people prepare might be reviewing a slide deck that shows the latest market trends, scanning a white paper about nanotechnology, watching a short documentary about a company that gets culture right, responding anonymously to survey questions that can be shown in session, recording a video for people to review at their leisure, or asking people to source examples of products that inspire them and may contribute to ideation in an innovation session. We live in a multimedia world so I often encourage meeting planners to take advantage of that. You can get usefully informed on some aspect of a meeting through a YouTube video, a Substack post, or a podcast.

Of note: If you’re going to make the success of the meeting contingent on people doing their pre-work, give them fair notice - multiple days in advance. And make the relationship between the content they’re consuming and the Purpose and Product of the meeting itself abundantly clear. In other words, motivate them and set them up for success through clear communication.

PRACTICAL CONCERNS

Practical concerns are just that - the nuts and bolts, the time, place, and material requirements for a meeting to be successfully executed. Your game sequence will take place inside of some environment - analog or digital - so that environment and its resources need to be known as roundly as possible. A short story will drive this point home.

One of the authors of this book - Sun - is credited with being the first person to bring graphic recording and graphic facilitation to the SXSW Conference in Austin, Texas. She introduced large-scale visual thinking to the organizers in 2009 and worked with them for several years. Eventually, other practitioners were inspired and got involved, so visual thinking teams spread into various avenues of the conference.

Here’s an example that stresses the importance of considering the practical concerns. One of the later visual thinking teams for SXSW lived in New York and hadn’t been onsite in Austin or designed visual-thinking sessions in-the-flesh at the conference, which resulted in a sizable blooper: The team made unconscious assumptions about the physical space. They didn’t anticipate the sheer size of the convention center in which the conference was held, didn’t ask for site maps for sessions inside or outside of the convention center.

As you might imagine, this seemingly simple omission affected the outcome in a significant way. This team had agreed to be the visual practitioners for any session SX requested - another error that could have been anticipated in the Preparation stage - and they dramatically underestimated how long it would take to move a team member and her visual materials from one room to another. As a result, team members were all over the place. They were late to many of the sessions, missed some of them entirely, arrived at some without meeting supplies, and they were scrambling, running around trying desperately to make it all work. The team members grew sweaty, exhausted, and frustrated and that, of course, impacted performance.

This was a foreseeable outcome had they anticipated one of the most crucial questions involving meetings in the real world: the dimensions of physical space. One basic error like this can have a cascade effect on almost everything, so be rigorous about asking logistical questions. Don’t just imagine the space you’re working in - get pictures of it. Find the dimensions or sitemap online. Ask the hotel onsite event coordinator to send you everything he has about the space. Find out where the stage will be. The speakers. How much privacy do you have? What size tables are you working with? Will people need microphones? How and when might other traffic be moving through? What is there to project slides onto? How far away are breakout rooms? WHERE ARE THE BATHROOMS? WHERE IS COFFEE?! And what are the equivalencies in digital meetings?

All of that will need to come together for a hearty gamestorming session. Sometimes it’s simple - your team is simply assembling in your regular reserved space - and other times much of this is handled by reliable, vetted people or even an events team. But sometimes it’s not. Know what you’re getting into and check your assumptions.

Even though other folks who aren’t responsible for the meeting may not understand your questions, when planning a meeting onsite or online, be thorough almost to a fault. Ask questions of people on the ground and in the know, even if they roll their eyes about your fixation on log-in protocols, room acoustics, the food menu, or lighting. When the people finally arrive in the room and they’re ready to get to work, the less surprises, the better. There are detailed meeting checklists for onsite and online gamestorming sessions. Start with those and modify them as you develop your personal approach and style.

PITFALLS

In many ways, Pitfalls are the result of what happens when we don’t spend sufficient time considering the other P’s. Pitfalls can be technical, social, logistical, political, material, financial. There are myriad ways to unintentionally misstep so whether you’re gamestorming in the real world or a digital environment, it behooves you to try and anticipate pitfalls of various shapes and sizes.

As you start to experiment with gamestorming in the true arena of meetings and workshops, you’ll quickly discover that the diversity of possible pitfalls is boundless, so agility and improvisation ultimately become your best friend. I can tell that someone has become more masterful at meetings when they’re unflappable no matter what happens, and they stay calm and meet each moment. It takes time, experimentation and trust to get there. En route to greater confidence, anticipating and scenario-planning pitfalls is a very good practice. Edward De Bono calls this ‘black-hat thinking’ - anticipating what could go wrong - or you can think of it as a light version of Red Teaming - a model for roundly challenging significant aspects of a plan.

Below are examples of common pitfalls that can be avoided with a little preparation:

Not having detailed knowledge of either the onsite location or the online equipment and its functionality

Leaving the design of the agenda until just a few days before a workshop that’s either large, long, or complex

Letting one group overwhelm the presence or contributions of another without having a plan to address that circumstance

Failing to consider who’s sitting where, with whom, and why

Not connecting meaningfully with your co-facilitator in advance, to discuss how you’ll “dance” together if X, Y, or Z occur

Neglecting to consider acoustics and lighting in the room

Inviting the wrong people or forgetting to invite the right people

Being insensitive to power dynamics

Avoiding an elephant in the room that’s occupying everyone’s awareness and making it difficult for them to focus

Being oblivious to cultural norms - this doesn’t mean you obey them all the time–it can be healthy to challenge norms for the sake of learning–but in order to sustain the confidence of the group, be aware of what norms you’re challenging and why

Including too many people on the design team

Socializing the meeting purpose and goals with the wrong stakeholders or with too many stakeholders

Not getting clear on the requirement for materials - gamestorming is a multi-sensory, hands-on way of working. If you have 16 round tables in a session and only two flip charts and four markers, well, you see the problem. If your digital whiteboard has game spaces that only accommodate 20 sticky notes and each group is likely to generate 100 sticky notes per game space, that’s also a problem.

We cannot stress enough how helpful it is to anchor your meeting design with the 7Ps.6 It is the scaffolding on which good (or at least better) meetings are built. Keeping it in mind anytime you plan to gather is one notable way to demonstrate respect for the people you’ve invited. The 7Ps are so natural that as soon as you see the framework, it will almost immediately become intuitive, like a language you once knew but somehow forgot. To enhance your love for it, below is a rapid approach to identifying which meetings in your team or organization at large you’d like to rework with a little gamestorming mojo.

Post-up

Start by brainstorming all types of meetings you’ve noticed in your organization. Think through a typical day, week, month, quarter, a year. How many distinct kinds of meetings can you recall? Write down one meeting type per sticky note.

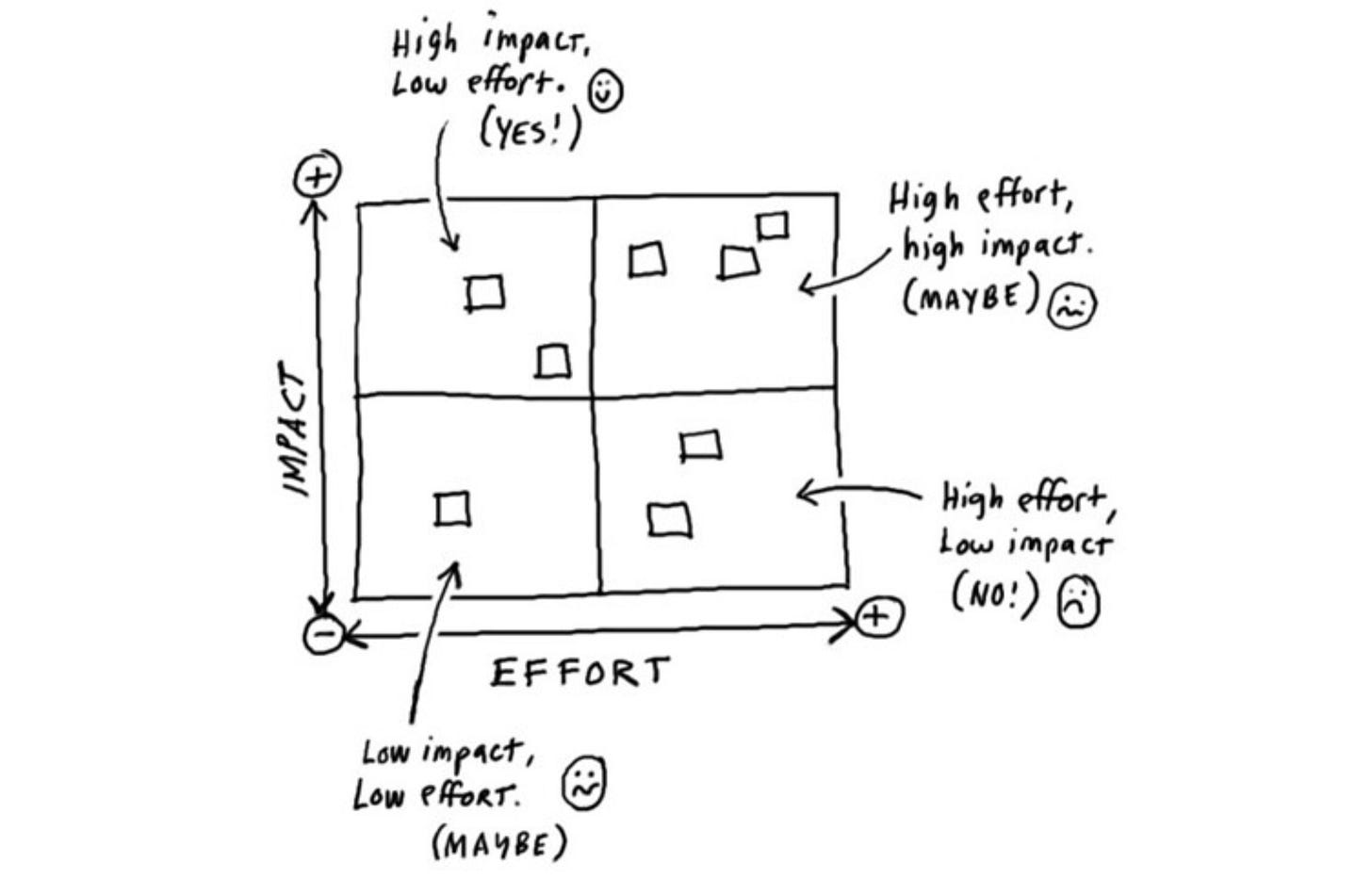

Prioritize

Use the Impact/Effort Matrix to prioritize these meeting types. Which meetings require the least effort to change? Which meetings could have the most impact on culture and behavior? Select the meeting(s) you want to rethink and redesign.

Plus/delta

After you run your meeting, get feedback from participants so you can improve for next time.

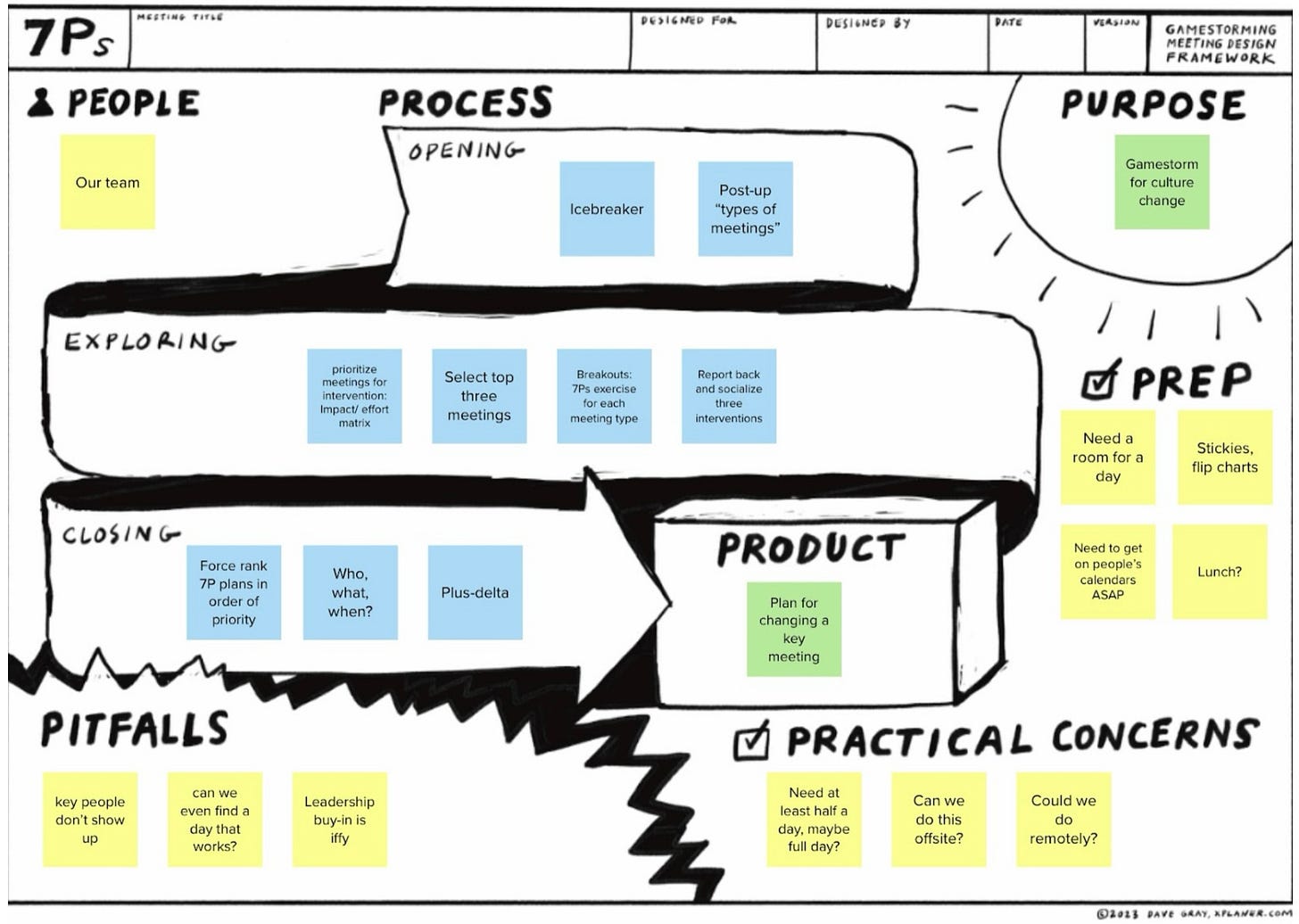

Just to be a bit meta, Figure 12-5 shows how you might use the 7Ps framework to design this kind of intervention experiment.

Virtual meetings

As we have conducted Gamestorming trainings all over the world, one question has come up more than any other: “How can we use this with virtual, distributed teams?”

The good news is that the technology for virtual meetings has advanced rapidly since we first published Gamestorming in 2010. If there’s a silver lining to the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s that most people have become accustomed to virtual meetings. Many people now have a dedicated office set up, with camera and microphone, and are increasingly well-versed in attending meetings online. So we now have solid responses to the question of virtual meetings that we didn’t have in 2010.

Virtual meetings come with a different set of constraints and opportunities. Of course, in many ways, there is no substitute for meeting in person, if you can manage it. But if your team is distributed, there’s a lot you can do to introduce Gamestorming principles for better engagement and productivity.

Gamestorming for virtual meetings and events

So how can you use Gamestorming to design and facilitate better online meetings and events?

It’s important to recognize that virtual meetings are their own animal. They have different properties, and because of that, they need to be approached differently.

With virtual meetings, for example, the stress and expense of travel and accommodations is eliminated, but at the same time, you lose the intensity and focus that comes from getting people into a room for a condensed period of time.

When people are working at home, office distractions are reduced, but there’s a greater chance that people’s home lives and circumstances will intrude on the meeting.

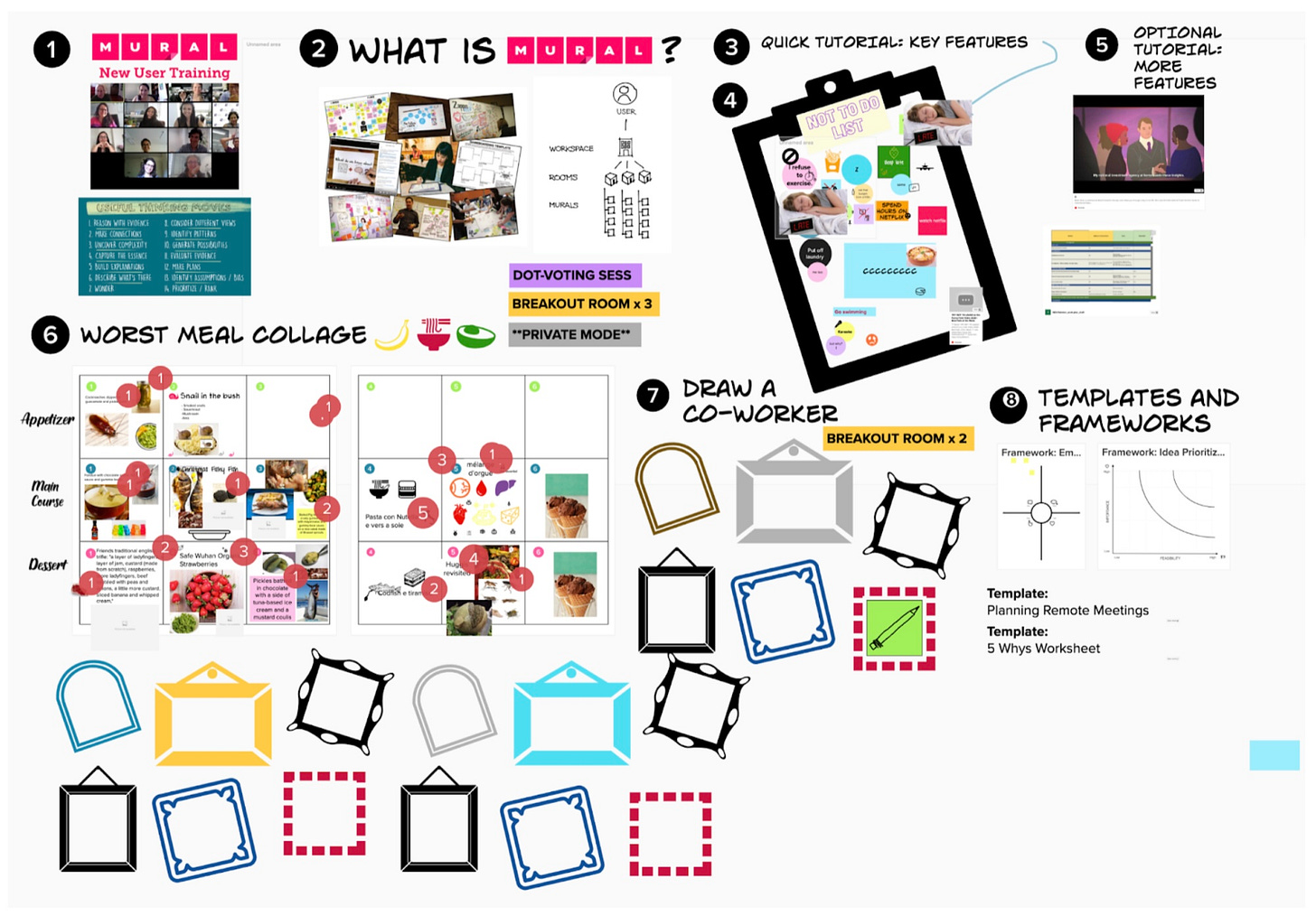

The two tools that we have found indispensable are video meeting apps, like Zoom or Microsoft Teams, and online whiteboards such as MURAL or Miro. These tools work best in combination, allowing people to see and hear each other while providing a space for them to work and think.

Be aware that virtual meetings take a toll on people’s attention and energy. After a lot of experimentation, trial and error, we recommend you schedule Gamestorming meetings in 90-minute sections. Why 90 minutes? Since most people are accustomed to hour-long meetings, when you claim 90 minutes you are setting an expectation that this is a more serious time investment. At the same time, limiting the time to 90 minutes is respectful of people’s time and energy investment. We have found that when you go over 90 minutes, attention and energy start to wane, and beyond this timeframe, you reach a point of diminishing returns.

If you have more than 90 minutes worth of work, you can break the work down into multiple sessions. We have conducted successful workshops, even intense ones such as strategic planning sessions, by shifting what would have been a 2-day offsite into a weeklong sprint, by scheduling morning and afternoon sessions with breaks and homework in between sessions.

Group thinking

We think not just with our brains but with spaces, things, and other people. So in your design, it pays to think about all three.

Can you create a meaningful space for people to think in?

Online whiteboards, like MURAL and Miro, can offer great thinking spaces. In some ways, these whiteboard apps are better than real-life whiteboards.

First, they are persistent. You can more easily can set them up and organize them in advance of the meeting, and they can remain online indefinitely for later updates and elaboration.

Second, text that people input on sticky notes is easier to read, and, thanks to AI, also easier to harvest and summarize. Online whiteboards will often also accommodate other things that are useful to facilitators, like timers, dot-voting, and the ability to lock down elements that you don’t want moved.

Ninety percent of the success in any meeting is based on your preparation: what you do in advance of the meeting, deciding who to invite, how to set expectations, setting up the working area, thinking about timing, and so on. We like to think of the virtual whiteboard as the area to think through all this scaffolding to ensure your meeting is a success.

We like to make an agenda with sticky notes, with approximate times for each section. Be sure to leave a bit of extra time for the random noise as people enter the virtual space, fiddle with their technology, and get accustomed to the virtual environment. You can also assume it will take some time to switch between tasks, like moving from one exercise to another, opening breakout rooms, and so on.

Use the virtual whiteboard as a thinking and planning space for your meeting. Make space on the whiteboard for each game, exercise, or task. Populate the board with documents or presentations that you will want to refer to in the meeting. If the board feels overwhelming, you can hide certain sections by covering them with a white rectangle and revealing them as you get to them.

Too much detail can be overwhelming, while too little can create anxiety for participants. Strive for a “just right” level, where you have everything you need as a facilitator, and a structure that people can follow, without creating a lot of distractions.

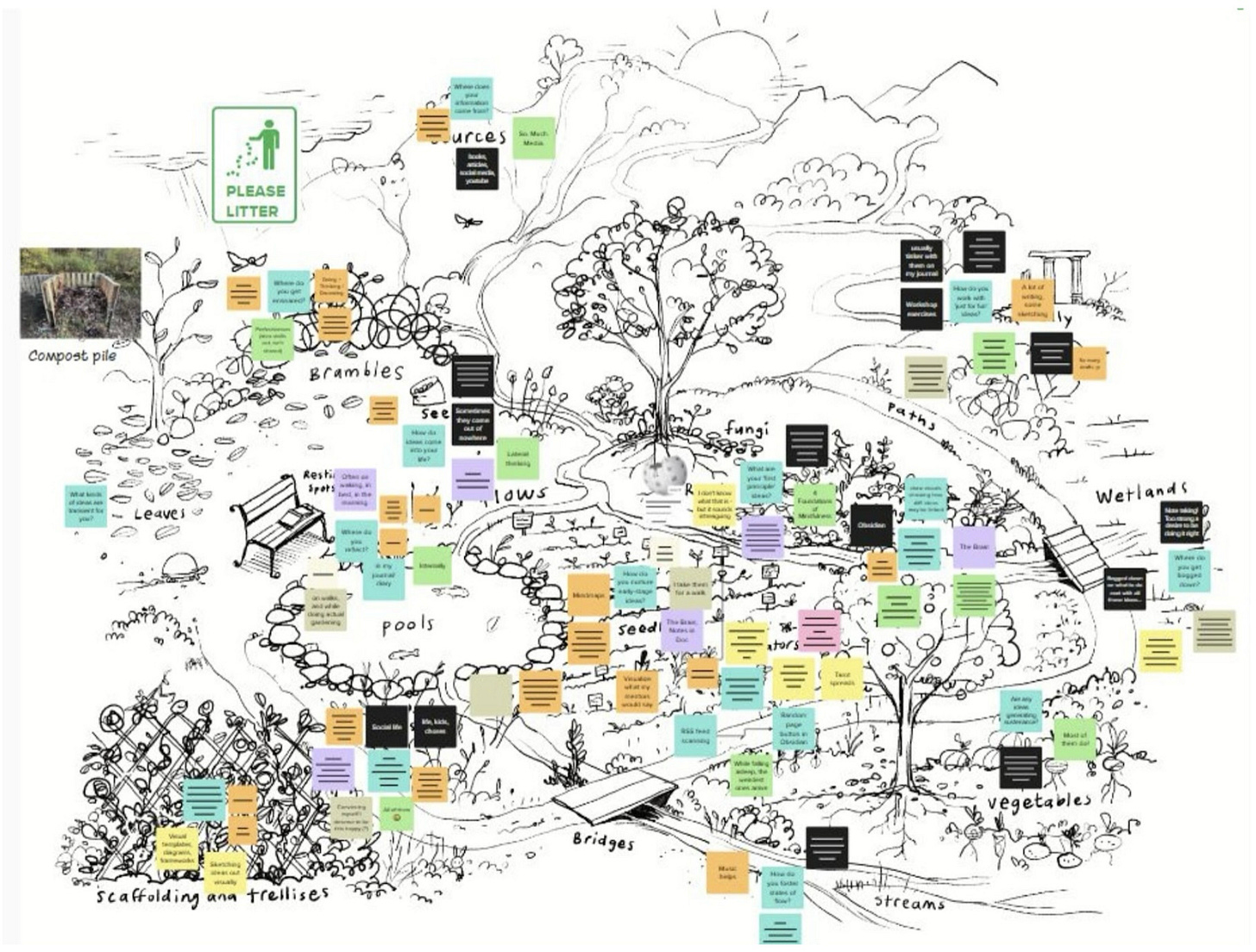

When appropriate, have fun with designing spaces for people to think in. For example, when we hosted a meeting about note-taking, we visualized a metaphorical “knowledge garden” for people to explore, with prompts for things to think about, like sources of knowledge, seeds of new ideas, harvesting fruits and so on. Someone in the session noticed we forgot a compost pile for old ideas, and they added it! One of the great things about metaphors is that they empower people to extend the metaphor in this kind of way.

A virtual thinking space designed to get people into a playful and exploratory mood.

If people are new to online meetings, make some time at the beginning of the meeting for people to get comfortable with the tools and ask questions. You can combine this “onboarding” to virtual tools with icebreaker exercises. For example, make a space and ask people to make a sticky note with something they;be been thinking about, or ask them to post a “behind the scenes” photo of their home office to the whiteboard. Consider the exercises you have planned and tailor your icebreakers to make sure people have a lighthearted, playful way to try out the tools. Watch what happens, and you will get a good sense of how capable people are with the tools. Based on what you see, you can ask someone to provide additional support in private chat or adjust your exercises if necessary. It can be helpful to have a few “how-to” videos available, which you can share in advance of the meeting.

Can you provide things for people to think with?

The most common “thing” that enables thinking is the sticky note. Sticky notes allow people to capture their thoughts in a modular and concise way, so they can be arranged, configured and organized in various ways. The ability to work with sticky notes is a core element of the Gamestorming toolkit. Online whiteboards make this as easy as double-clicking the background.

But you don’t need to limit yourself to sticky notes. You can provide background data in the form of documents, spreadsheets, slide presentations and web links, simply by copying the URLs and pasting them into the whiteboard.

Consider providing space on your whiteboard for each activity. Remember that some people in your group will probably be introverts. Give them some quiet time to think. Individual exercises are a great way to make space in your meetings. Give people a space to think in and ask them to think with sticky notes.

Here’s an example of a “thinking space” designed for individuals to share ideas. To create a feeling of a museum or art gallery, we used our visual skills to draw “security guards” and asked people to think about things they collect. We gave them five minutes and played some relaxing music while people populated the space with their ideas.

Resist the urge to talk while others are thinking! As a facilitator, you may feel the need to “fill the void” with small talk. Don’t do it. Your chatter will distract people from their task. If it helps, consider playing some wordless music, like jazz or something instrumental, while people are working on solo tasks.

Can you make space for thinking with people?

Don’t underestimate the time people will need to socialize new information as they are absorbing and synthesizing new ideas. Virtual video apps like Zoom and Microsoft Teams allow you to create breakout rooms for small-group discussion.

Breakout rooms give people — especially extroverts – a way to process new ideas and information. Some people think best through conversation. It can be very helpful to hear what others think, how they might apply a new idea, how it will fit into their workflow, and so on.

We suggest that you keep instructions for breakouts simple and only ask people to do one task, or answer one question, at a time. If instructions get too complex (such as, do this, then do this) it’s better to schedule multiple breakouts and sequence them, with a short break in between.

A note about hybrid meetings:

One important thing to keep in mind is that Gamestorming works best when there’s a level playing field. If everyone is joining remotely, you have a level playing field. The same is true if everyone is attending in person.

But what if some people can attend in person but some must join remotely? This is a judgment call and depends on the importance of the meeting and how important it is that everyone be fully present.

If the meeting is equally important to all participants, consider allowing everyone to work from home on that day, or (if it’s possible) requiring everyone to attend in person.

If a hybrid meeting is unavoidable, the in-person participants will have an advantage. In such cases there are a few things you can do to mitigate the asymmetry of the meeting. Technology can work to your advantage here. For example, you could use an online whiteboard to capture ideas and project the whiteboard on a screen for in-person participants. You can invite people in the office to bring their laptops and work on the shared whiteboard. If you can, set up a camera and microphone in the work room so remote participants can see what’s going on.

As we write this in 2024, virtual meetings and remote work are common, and likely to become more so. The more comfortable you can get designing and facilitating online meetings, the better.

We recommend thinking about virtual meetings not as a problem but as an opportunity. With virtual meetings you can use Gamestorming more often, in more meetings, to address more and different kinds of challenges. You can invite more people to participate and get more done. You can spend less time and money on the logistics, like travel, food, and lodging, and more on the quality of the online experience. Virtual meetings are not going away, so let’s go with the flow and embrace the magic that’s possible.

Pre-order your copy of Gamestorming 2.0 now!

Cal Newport’s advocacy of what he calls ‘deep work’ is an antidote to the continuous partial attention many of us are plagued with. The idea of ‘deep work’ is just as it sounds: It’s cognitively-rich work that purposefully blocks time and minimizes distractions in order to accommodate sustained, meaningful focus that results in higher productivity and more valuable output. Of note–Newport puts typical meetings in the category of ‘shallow work,’ a position we would not dispute.

Explore the research of Stuart Brown, M.D., Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Marc Bekoff, Jean Piaget, Dorothy and Jerome Singer, and Jaak Panksepp. From an excellent Newsweek article titled, Do You Play Enough? Science Says It's Critical to Your Health and Well-Being: “An embracing of joy and play is overdue, and not just because it feels good. Scientists have learned through a panoply of studies that the drive to play is a biologically hard-wired tool, common to almost all mammals, to promote experimentation, imagination, exploration and creativity. Play activates the reward centers of the brain, floods the rest of the brain with feel-good chemicals like dopamine and oxytocin and triggers the release of powerful neural growth factors that promote learning and mental flexibility. It causes stress hormones to drop, mood to lift and has an energizing effect.”

Alison Coward, Founder & CEO, Bracket.

Opening, Navigating, Examining, Experimental and Closing.

The language of ‘thinking moves’ is found in the book, Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for all Learners, funded by Harvard’s Project Zero. Also referred to as ‘thinking routines,’ these moves refer to habits of mind and cognition that support learning and engagement.

The 7Ps was an innovation by our original co-author, James Macanufo.

And, we're off. #gamestorming2.0